23 Oct A shoemaker’s quest to return manufacturing to New England (FDRA interviewed))

Doug Clark is a shoe veteran. During his 30-year career, the New England-based footwear maker has scoured Asia for affordable labor to make outdoor adventure shoes. He’s been to China more than 75 times.

But Clark has grown tired of training a steady stream of new workers. Even laborers earning $5,000 a year (a good salary by Chinese standards) weary of making shoes, which is laborious. Work rooms can be hot and dusty. Workers eventually want to move up the manufacturing food chain, to sit in quiet labs and assemble pristine tech parts for mobile devices.

“Taiwan, Thailand, China. Every single time, you train a new workforce. And the cycle is getting faster and faster,” Clark said. “The sustainable answer is to find a new process. It’s not to find a new workforce” in an untapped emerging economy.

Driven by a combination of factors, including new technology, rising production costs overseas and a growing appetite for “Made in USA” goods, Clark is doing something few American entrepreneurs have done in years: building a shoe manufacturing plant in the U.S.

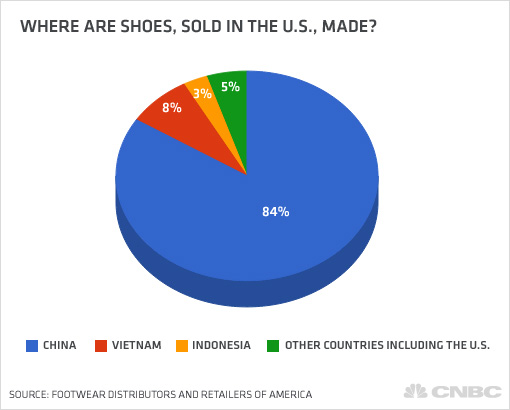

“That’s very rare these days,” said Matt Priest, president of the Footwear Distributors and Retailers of America. Roughly 99 percent of shoes sold in the U.S. are made abroad. “You can probably count them on your hands,” he said of the number of shoe factories remaining in the U.S.

Hoping to promote his planned factory and to generate money, Clark’s company, New England Footwear, is conducting a crowdfunding campaign that aims to raise $150,000 by Nov. 4.

Clark’s career path is in many ways a proxy for global manufacturing. In the 1970s, American footwear makers took the fork in the road to South Korea. Big global footwear brands set up shop there and eventually hopscotched to other Asian countries, including Taiwan and China, in search of lower labor costs. That is what footwear makers live and die by, as 40 to 50 parts must be assembled to make an average pair of shoes.

Today, though, more manufacturers are getting hit by the rising costs of doing business in China—especially small and midsize businesses, which can’t absorb macro-economic trends. China’s annual consumer inflation rose to a seven-month high of 3.1 percent in September.

As costs there rise, China can charge more for products and services. That spells bad news for U.S. consumers looking for inexpensive merchandise at big-box retailers—and for American entrepreneurs doing business on the mainland.

Fueled in part by rising inflation, China’s market share of footwear manufacturing has been declining. About 84 percent of shoes sold in the U.S. are made in China—the lowest level in seven years, according to data from the Footwear Distributors and Retailers of America.

More footwear makers are thinking they need to diversify beyond China, according to Priest. The association’s annual “Footwear Traffic, Distribution” conference ends Wednesday, and a lot of talk at the gathering, in Long Beach, Calif., has been about seeking new solutions to rising costs.

“People are looking at a lot of alternatives: Nicaragua, Ethiopia, Cambodia,” Priest said. “It’s a different and dynamic time.”

(Read more: ‘Made in USA’ fuels new manufacturing hubs in apparel)

New England’s shoe manufacturing roots

While many footwear makers are looking to new production regions, Clark is betting on New England, which has rich manufacturing roots. Most innovations in shoemaking came from there between 1880 and 1970. A key development was a “lasting” machine, invented in 1888 in Lynn, Mass. It stitched the upper parts of shoes to soles, paving the way for affordable, mass-produced footwear.

More than 15,000 factories flourished in New England up until the 1980s, but the appetite for innovation receded incrementally. Clark, a history buff, graduated from the University of New Hampshire in that decade and landed his first job as a technician at Nike’s research lab in Exeter, N.H.—since relocated to Portland, Ore.

Clark learned the fundamentals of shoe design, every stitch and seam, and how it affects the wearer’s performance and comfort.

But while Clark was tinkering and testing, shoe factories nearby were shuttering. He was already seeing the cracks in the industry and the consequences of shipping production jobs overseas.

“Even in the ’80s, we knew there was something wrong,” he said. “It’s crazy that we let this industry slip away here.”

This is where Clark’s manufacturing dream comes into play.

By the mid-2000s, Clark was leading innovation at another outdoor footwear and apparel company, Timberland. The task at hand was to remove cement from a shoe prototype. (If you’ve ever wondered why some shoes are as heavy as bowling balls and never seem to wear out, it’s because roughly 30 percent of the weight in an average shoe is cement.)

Removing the cement and eliminating related manufacturing steps, such as excessive stitching and costly steel molds, resulted in a lighter but still sturdy shoe, produced with 50 percent less labor than required in traditional shoemaking. Such innovation is sometimes called smart, or lean, manufacturing.

“I thought, ‘Wow. We designed a lot of labor out of there,’ ” Clark, now 57, recalled. “And if you don’t need labor, you don’t need China.”

Clark eventually bought that innovative technology from Timberland and founded his own active footwear company in 2008.

Last week, Clark moved his 12 employees to New England Footwear’s new, 10,000-square-foot headquarters—offices and a warehouse—in Stratham, N.H., southwest of Portsmouth. The goal is to buy equipment and build an additional 6,000 square feet to make footwear locally.

Clark estimates that the new factory will employ about 200 workers, and his goals include moving half of his production back to the U.S. from China by 2017.He ultimately wants to bring it all back.

Clark’s technology will increase productivity and remove about 70 percent of the labor required versus conventional “cut, glue and stitch” processes used in Asian factories. Based on New England Footwear’s productivity upgrades, shoes made domestically will have almost the same labor costs as those made in Asia.

“We will pay our employees about $30,000 a year here in New England, versus $4,500 a year, which is the average wage in China right now,” Clark said. The idea is to share the cost savings from better production methods in the form of higher wages to American workers.

Reshoring, and a little help from China

Clark estimates the new shoe factory will cost roughly $5 million. And in an unexpected twist on the “Made in USA” movement, the small-business owner so far has two investment offers from Chinese companies.

Clark has talked to some 50 American private equity companies and has “zero offers,” he said. “In some way, it’s ironic.”

Potential investors are skeptical about a broad consumer appetite for American-made goods, he said, “but I believe there’s never been a better time,” Clark said.

Some recent research bears out that forecast.

The Boston Consulting Group found that most U.S.-based manufacturing executives plan to bring production back to the U.S. from China or are actively considering it. The survey, conducted in August, focused on companies with sales of more than $1 billion.

The survey results, released last month, showed a 47 percent rise in “reshoring” consideration among respondents in 18 months. The percentage of executives, who are already moving production to the U.S. from China, or who plan to do so within the next two years, more than doubled, to 21 percent, during the period, according to BCG.

Key factors in reshoring—or the reversal of overseas outsourcing—include labor costs, proximity to customers and product quality.

“The most fundamental drivers of reshoring are the increasing competitiveness of U.S. labor rates and very cheap energy costs to manufacture in the U.S.,” said Justin Rose, a Chicago-based partner for BCG and a co-author of the research. The unlocking of shale oil and gas reserves has helped lower U.S. natural gas prices, an important factor in a lot of manufacturing, he said.

BCG also estimates that wage and benefit increases of 15 percent to 20 percent a year at an average Chinese factory will slash China’s labor-cost advantage to 39 percent by 2015 from 55 percent today.

But Clark didn’t need a study to tell him what he has suspected for years: The math of manufacturing in China is changing.

In Clark’s crowdfunding effort to raise money as well as awareness for his U.S. factory, a $45 donation gets you a pair of the first U.S.A.-made Comp XT shoe models. A gift of $65 gets you a pair of of Asian-made Comp XTs. The shoes retail for about $120.

The entrepreneur’s pitch on Indiegogo is simple: Buy a pair of his shoes, and help bring footwear manufacturing back to the U.S.

It has been 40 years since shoemakers began fleeing to Asia, “and I’m tired of it,” Clark said. “We have to find a way to be more productive here.”